[ad_1]

Some fake content posted online is based on our desire for social justice. In a web where we are supposedly looking for more authenticity, does the spectacle of our values take precedence over reality? This is the subject of the Rule 30 newsletter this week.

During my vacation, I thought a lot about lies. Those from my Instagram account, when I shared photos of a lovely meal in the sun (a few hours later, I was bedridden by violent sunstroke). Those that I saw pass through my news feed, like this video from an American media outlet calling for a boycott of the Olympic Games, widely shared in left-wing circles (it was in fact an influence operation potentially funded by an Azerbaijani entrepreneur). Those of Elon Musk (there are too many to detail).

This article is an extract from #Rule30. Our newsletter is sent every Wednesday at 11 a.m.

Of course, we lie online and off. But the internet has a special relationship with lies. On the one hand, people caught lying to others are very criticized. On the other hand, we enjoy being fooled, including by ourselves.

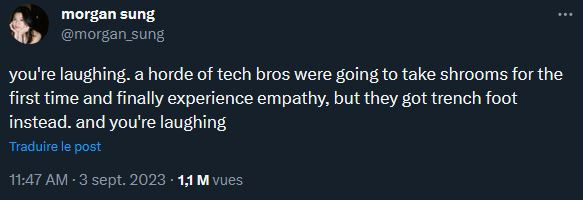

Being delulu is the solulu (being deluded is the solution), TikTok has been screaming at me for months. We want to believe that we didn’t finish this charming lunch with our noses in the toilet bowl, that the whole world is worried about police violence in France, that people who are too rich kill each other at Burning Man or that Elon Musk is going to get his face beaten by Mark Zuckerberg. We know it’s not true, but we play the game anyway.

A recent article from the magazine Rolling Stone illustrates this phenomenon. We learn there that there is a small industry of fake “Karen” videos. This meme originally referred to a white woman who behaved selfishly and rudely, particularly towards people in service jobs, for example, a cashier or a waiter at a restaurant.

Then it took on a connotation much more serious in 2020, becoming a symbol of the racism of white women who take advantage of their privileges to verbally or physically attack racialized people. At the time, the term provoked a debate about its potential sexism (on this subject, I recommend to read this article by the late Bitch Media). Today, almost everyone agrees to criticize the Karens, and it is common to come across videos of strangers with erratic behavior that Internet users make fun of.

Sometimes it’s completely bogus

Except that sometimes it’s completely bogus. The article of Rolling Stone notes several examples of Karen’s videos that were shot in a studio, with the sole purpose of going viral online. Often, it is quite easy to detect that these contents are fake. But most of the time, the audience doesn’t care. “ However, there is no shortage of true examples of white women who treat poorly those with less power than themselves.“, concludes the article. “ Maybe people online don’t really want these people to be held accountable for their actions in real life. All that matters is the show. » In other words, we like to show that we are indignant, and we also like it when it entertains us.

This is where, if I may say so, lulling yourself with illullu is not the solution. Online misinformation is a complex subject and takes many forms, not just deepfakes of Emmanuel Macron (a phenomenon which is also much rarer than video rigging for the purposes of sexual harassment). It is not always rooted in hatred of others, but also in our desires for social justice.

Above all, it is monetizable. On Twitter/X, a verified account can now claim part of the advertising revenue earned by its most viewed tweets, as is already the case on YouTube, TikTok or Instagram. We learned (with difficulty) that reacting to violent messages increased their virality. But do we want to distinguish false injustices from real ones?

Do you want to know everything about the mobility of tomorrow, from electric cars to e-bikes? Subscribe now to our Watt Else newsletter !

[ad_2]

Source link